Phoma is a genus of fungal organisms that is widespread throughout the world – its species are commonly found in soil, organic matter, plants and also in aquatic environments. Many species of Phoma are important plant pathogens, known to contaminate food sources such as maize and potatoes.

Furthermore, several species can be pathogenic to animals and humans. This article will provide a short overview of the Phoma genus, discussing its most important species, dangers to humans and ways of treating it.

What is Phoma?

Phoma is a diverse group of filamentous fungi first identified in the beginning of the 19th century [1]. However, the Phoma name was introduced in 1880 by the Italian mycologist Pier Andrea Saccardo. The Phoma genus initially contained only plant stem pathogens, but nowadays this group comprises opportunists, pathogens and saprobes. Phoma is an anamorphic genus, meaning its members reproduce asexually. Their teleomorph forms are described in several other genera, including Didymella, Mycosphaerella, Leptosphaeria and Pleospora [2].

They are ubiquitous in nature and have cosmopolitan distribution, with many species existing as saprobes aiding the degradation of organic matter. However, many species are plant pathogens, and some can even switch between these two lifestyles depending on the availability of hosts [3].

Phoma are of significance to humans – not only do they parasite on several economically important crops, they also commonly grow in indoor settings and can potentially be hazardous to the health of their human cohabitants. However, human infections are rare and have been known to be fatal only in a small number of instances.

Phoma species

Phoma has always been considered as one of the largest fungal genera, with over 3000 different varieties described [4]. However, due to the fact that many varieties are named after the plant hosts they were isolated from and the fact that that their micromorphological characteristics vary greatly when observed in culture, the systematics of this genus is problematic and has never been fully understood [5]. Currently, more than 220 species are formally recognized [6].

More than half of these 220 species are known to be primary plant pathogens, many of them specializing on a single genus of plants. The most economically important phytopathogens include P. medicaginis, P. lignam, P. andigena, P. tracheiphila, P. foveata and P. macdonaldii [3].

10 species of Phoma are known to cause infections in humans, including P. glomerata, P. hibernica, P. minutella, P. eupyrena, P. minutispora, P. sorghina [7] and P. exigua [8].

In indoor settings, the most commonly occurring species are P. glomerata, P. herbarum, P. porporum var. porporum and P. eupyrena [3].

Phoma mold

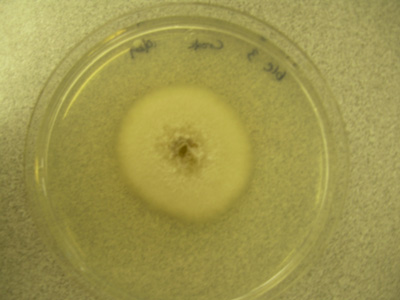

If provided with an adequate amount of moisture, Phoma will develop into a visible fungal growth commonly known as mold. In indoor environments, Phoma is commonly found on damp or water damaged structural materials, such as concrete, wood, fibreglass, plaster and wallpaper [9]. It can also be found on painted surfaces, window frames, carpeting, and linoleum and is frequently isolated from household dust [10].

Most species of Phoma grow optimally at temperatures ranging from 26 to 37°C, and at a water activity around 0.90. Colonies often have a velvety or powdery texture and are pale to reddish-orange in colour, becoming greenish-gray to dark brown to black as they mature. They are also known to produce pink and purple spots on painted walls due to the presence a diffusible pigment [10].

Phoma species are common agents of food spoilage and can develop on a variety of fruits, vegetables and dairy products. Phoma has been known to contaminate seeds, nuts, soybeans, potatoes, bananas, sorghum, maize, kiwi berries, lemons, tomatoes, eggplants, and pomegranates. They can also colonize man made aquatic environments such as water distribution systems and swimming pools [11].

What are Phoma health risks and dangers?

Most species of Phoma are saprobes, contributing to the decomposition of organic matter in nature and playing an important role in nutrient cycling. However, some of them are known to occur in living tissue, either as opportunists or as primary pathogens. Interestingly, many species can switch between the two lifestyles, living mostly as saprobes but switching to a parasitic lifestyle when suitable hosts are present [3].

As human infections are uncommon, most of the dangers associated with Phoma are related to its role as a plant pathogen.

P. sorghina is a common contaminant of sorghum, potatoes and maize [11]. P. lignam is the most important pathogen of canola, leading to yield losses of up to 25%. Aside from these direct losses, millions dollars are also lost annually due to quarantine restrictions. Namely, quarantine regulations are in place in order to prevent the introduction or spreading of pathogenic Phoma species.

Shipments that are suspected of contamination can be refused or destroyed, leading to additional costs for importing and exporting traders. Phoma is also associated with several animal diseases, such as bovine mycotic mastitis and fish mycosis in salmon and trout [3].

Cases of human Phoma infection are rare. Most cases of Phoma infection in healthy people involve trauma and are limited to the skin, ranging from superficial lesions to persistent subcutaneous infections. Phoma can also cause eye infections (keratitis), usually due to trauma or use of contact lenses [10].

Unlike most other types of molds, the respiratory organs are rarely the route of infection when it comes to Phoma. Despite this, several cases of lung infection have been reported, two of which resulted in the growth of a fungal ball in the lungs [8, 12].

Similar to other types of fungal pathogen, Phoma is a greater risk to individuals with weakened immune systems. This can be due to HIV/AIDS, chemotherapy, diabetes, use of oral steroids, or receiving an organ transplant. Although the mortality rate of Phoma infection is far lower than that of other common fungal pathogens, all fatal cases were reported in heavily immunocompromised cancer patients [11].

Furthermore, several species of Phoma produce harmful mycotoxins, such as cytochalasin A and B, deoxaphomin, proxiphomin and tenuazonic acid. No cases of human or animal mycotoxicosis have been confirmed to be associated with Phoma. However, reports suggest that tenuazonic acid secondary to ingestion of P. sorghina infected grains may be the cause of a form of thrombocytopenia in humans known as “onyalai” in Brazil and Central Africa [10, 13].

Phoma allergy

Although Phoma spores are not easily aerosolized, they are still considered to be common airborne allergens. They can cause hay fever and asthma and have been associated with hypersensitivity pneumonitis [10]. A Canadian study showed that in a group of allergic rhinitis or asthma patients for whom skin tests were positive to airborne fungal species, 36% were positive to P. glomerata – despite the fact that this species was isolated in less than 1% of outdoor and indoor air samples [14]. Therefore it is evident that the allergic potential of Phoma is higher than could be predicted by its airborne concentration.

Antibodies to Phoma have been isolated from individuals suffering from hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Interestingly, Phoma species have been isolated from the shower curtains of people suspected of having allergic interstitial pneumonitis, suggesting that moldy shower curtains could be a source of allergy [10].

How to treat Phoma?

Like all molds, Phoma prefers areas with sufficient moisture. The best way to avoid trouble related to mold is to keep your house dry and deal with and leaks or moisture issues as soon as possible. If you don’t, a Phoma colony can appear within a matter of days. It is a good idea to perform routine mold inspections of any areas of your house that may come into contact with water, such as bathrooms, kitchens (especially areas under sinks), window frames and basements. Also, air conditioning units should be regularly serviced, as the condensation that forms inside them provides an ideal environment for Phoma development.

If you catch a mold growth in its infancy, you may be able to remove it yourself by using a brush and a solution of water and household bleach. Apply the solution generously and brush until there are no more traces of the growth. However, this will likely result in the release of spores into the air so it is advisable to wear protective clothing and to use goggles and a respirator. The area should also be well ventilated.

If the problem persists or is already too large to handle, do not hesitate to call on the help of a professional mold remediation company like Mold Busters. Armed with 19 years of experience and the latest in mold removal technology, we are well equipped to handle a mold infestation of any size. To learn more about our comprehensive mold testing and removal services, call us today to book an appointment.

Did you know?

Chaetomium is the 2nd common toxic mold type found in homes we tested?! Find out more exciting mold stats and facts inside our mold statistics page.

References

- Sutton BC (1980). The Coelomycetes. Fungi Imperfecti with Pycnidia, Acervuli and Stromata. 1st edn. Commonwealth Mycological Institute, United Kingdom.

- Boerema GH (1997). Contributions towards a monograph of Phoma (Coelomycetes) – V. subdivision of the genus in sections. Mycotaxon. 64:321–333.

- Aveskamp MM, de Gruyter J, Crous PW (2008). Biology and recent developments in the systematics of Phoma, a complex genus of major quarantine significance. Fung Diversity. 31:1-18.

- Monte E, Bridge PD, Sutton BC (1991). An integrated approach to Phoma systematics. Mycopathologia. 115: 89-103.

- Aveskamp MM, de Gruyter J, Woudenberg JHC, Verkley GJM, Crous PW. Highlights of the Didymellaceae: A polyphasic approach to characterise Phoma and related pleosporalean genera. Studies in Mycology. 65: 1-60.

- Boerema GH, de Gruyter J, Noordeloos ME, Hamers MEC (2004). Phoma Identification Manual. Differentiation of Specific and Infra-Specific Taxa in Culture. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, UK. pp. 1-480.

- Howard DH (2003). Pathogenic Fungi in Humans and Animals. Marcel Dekker, New York. pp 666-667.

- Balis E, Velegraki A, Fragou A, Pefanis A, Kalabokas T, Mountokalakis T (2006). Lung mass caused by Phoma exigua. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 38: 552-555.

- Andersen B, Frisvad JC, Søndergaard I, Rasmussen IS, Larsen LS (2011). Associations between fungal species and water-damaged building materials. Appl Environ Microbiol. 77(12):4180-8

- D’Halewyn M, Chevalier P (2019). Phoma glomerata. Retrieved from inspq.qc.ca.

- Bennett A, Ponder MM, Garcia-Diaz J (2018). Phoma Infections: Classification, Potential Food Sources, and Its Clinical Impact. Microorganisms. 6(3).

- Morris JT, Beckius ML, Jeffery S, Longfeld RN, Heaven RF, Baker WJ (1995). Lung mass caused by Phoma species. Infect. Dis. Clin. Pract. 4: 58-59.

- Do Amaral AL, de Carli ML, Neto JFB, Dal Soglio FK (2004). Phoma sorghina, a new pathogen associated with Phaeosphaeria leaf spot on maize in Brazil. Plant Pathol J. 53: 259.

- Tarlo SM, Fradkin A, Tobin RS (1988). Skin testing with extracts of fungal species derived from the homes of allergy clinic patients in Toronto, Canada. Clin Allergy. 18(1): 45-52.

Get Special Gift: Industry-Standard Mold Removal Guidelines

Download the industry-standard guidelines that Mold Busters use in their own mold removal services, including news, tips and special offers:

Written by:

John Ward

Account Executive

Mold Busters

Fact checked by:

Michael Golubev

General Manager

Mold Busters