The kingdom of mold is home to many diverse organisms. Although almost all of them are useful to humans in an ecological sense, some species have made their way into industry, medicine and agriculture, even defining the way we live and see the world.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, also known as baker’s yeast, is an important ingredient in bread, a food that has been considered a staple of human life for thousands of years. Fermentation of grains to produce beer and of fruits to produce wine is an ancient art that humans in most cultures have practiced for millennia.

The impact of penicillin and other fungal antibiotics on 20th century medicine is more than evident. Fungi are also widely used for the production of many industrial chemicals. Furthermore, some species are able to degrade poisonous and pollutant compounds, leading to their use in bioremediation efforts of polluted soils.

This article will review the Beauveria genus, mostly known for Beauveria bassiana, a fungus widely used as a biological insecticide in agricultural settings.

What is Beauveria?

Beauveria is a genus of entomopathogenic fungi. They are parasites of insects and other arthropods. Beauveria species are anamorphs, meaning that they only reproduce asexually. Their teleomorph forms belong to the well known Cordyceps genus.

72 species are currently recognized in the Beauveria genus [1]. Among them, the most important are Beauveria bassiana, Beauveria brongniartii, Beauveria amorpha and Beauveria caledonica. Beauveria bassiana is by far the most well known species. Commercially available strains of Beauveria bassiana are often used as biological insecticides.

Where can Beauveria be found?

Beauveria bassiana has cosmopolitan distribution. It occurs naturally in soil around the world and is well known for its ability to colonize insects. However, this fungus can also grow on plants themselves, and has been isolated from several plant species, including rice, corn, cocoa, coffee, tomato, grapes, banana, sorghum and cotton [2, 3]. Beauveria has a general upper temperature limit for growth of 34–36°C [3].

Beauveria is not commonly found indoors. To the best of our knowledge, the only known record of Beauveria in an indoor environment is the isolation of its spores from mural paintings in European churches and monasteries [4].

Beauveria as a biological control agent

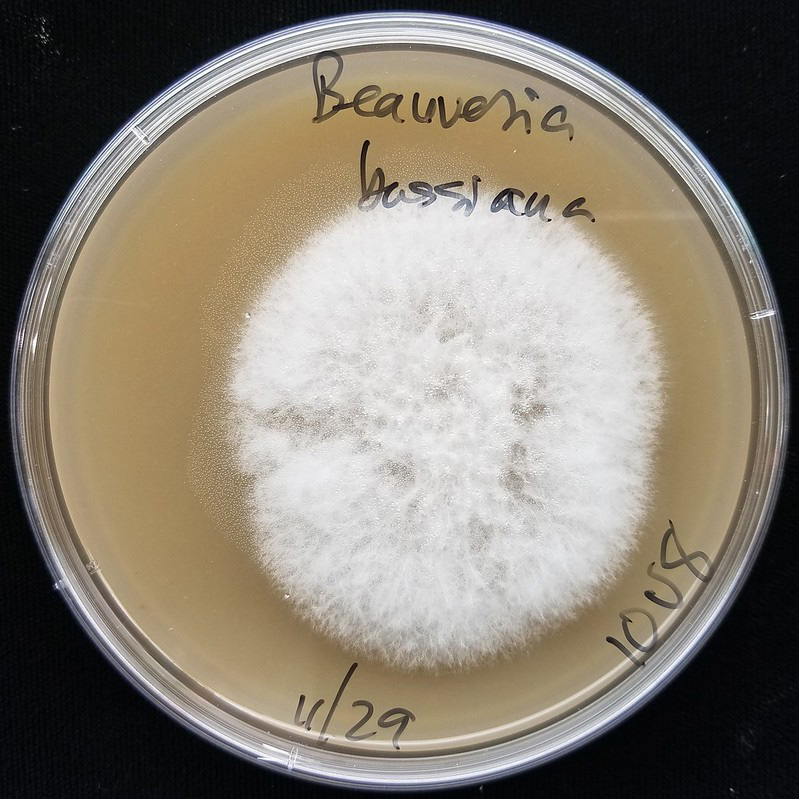

Beauveria bassiana is widely known for its use in as a biological control agent in agriculture. It was initially discovered in 1835 by the Italian entomologist Agostino Bassi. Bassi realized that this fungus was the causal agent of disease in Italy’s silkworm populations. The disease would cover the silkworms with a white powdery layer and was called white muscardine disease. The fungus behind the disease was subsequently named after Bassi [3].

One of the first and most prominent early attempts in extensively using Beauveria took place in the US Midwest for control of chinch bugs, Blissus leucopterus, in the mid-1800s [5]. The strength of Beauveria bassiana lies in its non selectivity towards its hosts – it can infect more than 700 species of insect, including common pests such as termites, thrips, whiteflies, aphids and different beetles [6].

Today, Beauveria bassiana is mass produced and various formulations are available, depending on the plants that need to be treated, the insects attacking them, and whether or not the plants are pollinated by insects (thus warranting a strain that will eradicate the pests but leave the pollinators unharmed).

The demand for chemical-free food and the rise of organic agriculture have lead to increased interest in developing microbial biopesticides, even among large chemical agricultural companies.

The global biopesticide market has been growing since the 1980s. Among the microbial biopesticides, fungi represented almost 19.4 % of the total biopesticides sold in 2010. Unlike viruses, protozoans and bacteria, which require specific routes of infection (i.e. through ingestion), the majority of entomopathogenic fungi infect arthropods by direct penetration of the host cuticle and thus function mainly as contact pathogens [3].

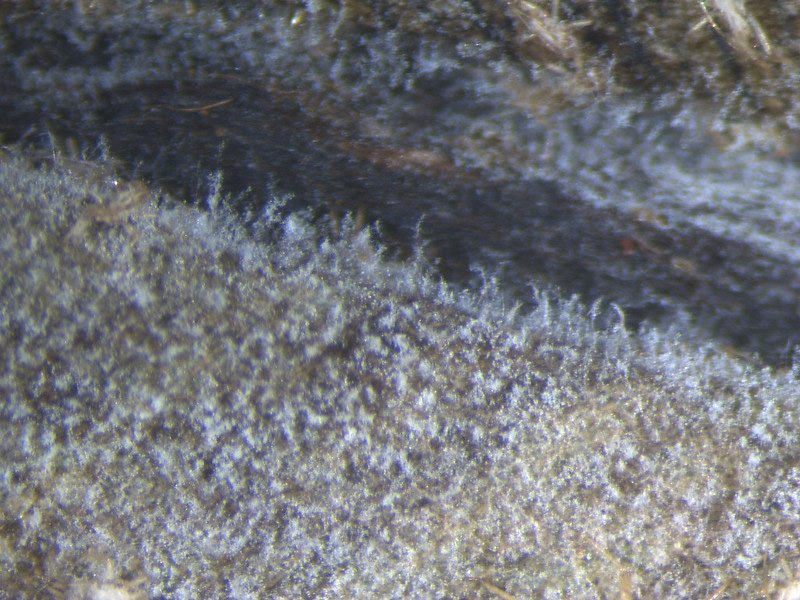

When spores of Beauveriax bassiana come in contact with the cuticle (skin) of susceptible insects, they germinate and grow directly through the hardened exoskeleton to the inner body of their host. Once inside, the fungus proliferates throughout the insect’s body, producing toxins and draining the insect of nutrients, which eventually leads to its death. Once the fungus has killed its host, it grows back out through the softer portions of the cuticle, covering the insect with a layer of white mold (hence the name white muscardine disease). This powdery mold produces millions of new infective spores that are released into the air when environmental conditions, especially humidity, are permissive.

Outside of agriculture, Beauveria bassiana has been used in the control of common household pests such as mosquitos and bedbugs. The spores of these fungi can easily be mixed with oil and then applied to surfaces such as the inside of a house similar to long-lasting insecticides. This approach exploits the resting behaviour of mosquitoes, which can often be found resting on walls indoors [7]. A preliminary evaluation of the potential of Beauveria bassiana for bedbug control showed that the fungus was highly virulent to bed bugs, causing rapid mortality (3–5 days) following short-term exposure to spray residues [8].

Health effects of Beauveria

Infections by Beauveria are extremely rare. It has been reported to be the cause of eye infection (keratitis) [9]. Only two cases of systemic human infection have ever been documented, both in heavily immunosuppressed patients with acute forms of leukaemia [10, 11]. Apart from these cases, the only other known instances of Beauveria infection occurred in captive reptiles, namely alligators and giant tortoises [12, 13].

Like all fungi, Beauveria reproduces by dispersing microscopic spores into the air. If inhaled, these spores can contribute to respiratory difficulties and allergies, just like almost any powdery substance. Despite being generally recognized as safe, Beauveria bassiana was shown to elicit one of the strongest reactions relative to the other fungal species tested in skin prick assays on patients with mold allergies. Furthermore, it has been confirmed that crude extracts of Beauveria bassiana can elicit allergic reactions in humans. Four potential allergens produced by this fungus have been identified [14].

Although commercial Beauveria based insecticides are considered to be safe, it is recommended to take precautions when using them. Individuals using Beauveria products are advised to wear long sleeved clothing, a dust filtering respirator, gloves and goggles when applying the biopesticide.

How to get rid of Beauveria?

Perhaps a better question would be where to find Beauveria! The popularity of this fungal insecticide has been rising massively in recent years. It is available to purchase under a wide variety of trade names depending on its producers.

If you are here because you have mold in your home, you shouldn’t be worrying about Beauveria. This type of fungus does not develop indoors. However, if you have any further questions about Beauveria or any other type of mold, feel free to give us a call.

Did you know?

Offices in Canada are the most affected by the Basidiospores mold group?! Find out more exciting mold stats and facts on our mold statistics page.

References

- Bensch K (2019). Beauveria. Retrieved from mycobank.org.

- Jia Y, Zhou JY, He JX, Du W, Bu YQ, Liu CH, Dai CC (2013). Distribution of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana in rice ecosystems and its effect on soil enzymes. Curr Microbiol. 67(5):631-6.

- Mascarin GM, Jaronski ST (2016). The production and uses of Beauveria bassiana as a microbial insecticide. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 32(11):177.

- Nugari MP, Realini M, Roccardi A (1993). Contamination of mural paintings by indoor airborne fungal spores. Aerobiologia. 9: 131-139.

- Lord JC (2005). From Metchnikoff to Monsanto and beyond: the path of microbial control. J Invertebr Pathol. 89:19-29.

- Inglis GD, Goettel MS, Butt TM, Strasser H (2001). Use of hyphomycetous fungi for managing insect pests. In: Fungi as biocontrol agents. Progress, problems and potential. CABI Publishing, Wallingford. pp 23-69.

- Blumberg BJ, Short SM, Dimopoulos G (2016). Employing the Mosquito Microflora for Disease Control. In: Genetic Control of Malaria and Dengue. Elsevier, London UK. pp 335-362.

- Barbarin AM, Jenkins NE, Rajotte EG, Thomas MB (2012). A preliminary evaluation of the potential of Beauveria bassiana for bed bug control. J Invertebr Pathol. 111(1):82-5.

- Kisla TA, Cu-Unjieng A, Sigler L, Sugar J (2000). Medical management of Beauveria bassiana keratitis. Cornea. 19(3):405-6.

- Henke MO, De Hoog GS, Gross U, Zimmermann G, Kraemer D, Weig M (2002). Human deep tissue infection with an entomopathogenic Beauveria species. J Clin Microbiol. 40(7):2698-2702.

- Tucker DL, Beresford CH, Sigler L, Rogers K (2004). Disseminated Beauveria bassiana infection in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Microbiol. 42(11):5412-5414.

- Fromtling RA, SD Kosanke, JM Jensen, GS Bulmer (1979). Fatal Beauveria bassiana infection in a captive American alligator. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 175:934-936.

- Georg LK (1962). Mycotic pulmonary disease of captive giant tortoise due to Beauveria bassiana and Paecilomyces fumosoroseus. Sabouraudia. 2:80-86.

- Westwood GS, Huang SW, Keyhani NO (2006). Molecular and immunological characterization of allergens from the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana. Clin Mol Allergy. 4:12.

Get Special Gift: Industry-Standard Mold Removal Guidelines

Download the industry-standard guidelines that Mold Busters use in their own mold removal services, including news, tips and special offers:

Written by:

John Ward

Account Executive

Mold Busters

Fact checked by:

Michael Golubev

General Manager

Mold Busters