Smuts is a plant-pathogenic group of fungi with significant economic importance. These fungi are characterized by the production of masses of dark, sooty spores called teliospores. The powdery masses of spores give the appearance of dirt or ash, hence the name smuts. They are best known for being pathogens of economically significant crops, such as maize, barley, wheat, oats, and sugarcane.

What are smuts?

Smuts are well-known crop and grass pathogens, characterized by the formation of dark, thick-walled spores called teliospores. Teliospores serve as overwintering propagules. There are approximately 1640 species that are regarded as ‘true’ smuts, most of them belonging to the Basidiomycota division. However, there are certain ascomycete members such as Schroeteria, which are referred to as smuts because they possess similar organization and life strategies. Smuts was formerly synonymous with the Ustilaginales order. However, recent phylogenetic analysis has shown that this is not the case and a restructure of their classification has been proposed [1].

The hosts of smut fungi are herbaceous plants, mostly belonging to the family of grasses (Poaceae). Over 40% of known species of smuts parasite on grass species, and a further 15% parasite on sedges (Cyperaceae) [2]. Only 11 species are known to parasite on woody plants and they mostly lack the ability to form teliospores [1].

Smut life cycle

Smuts develop on all above-ground parts of plants, including stems, leaves, and flowers. Infections are usually observed as dark masses of spores visible to the naked eye. Their development is often tied to that of their host and will often only be visible as the plant starts to flower or develop its seeds. Smut infection often results in abnormal growths of plant tissue, commonly known as galls.

Upon release, the teliospores are spread by wind, water, or animal vectors. When the spore reaches an environment with enough humidity, it germinates and begins developing into a mycelium, or in certain conditions, yeast-like structures, sporidia. When two compatible sporidia meet on a surface of a plant, they fuse and invade the host plant. Before fusion of spermatids and the formation of dikaryon (cells containing two nuclei) mycelium, sporidia can’t infect a plant.

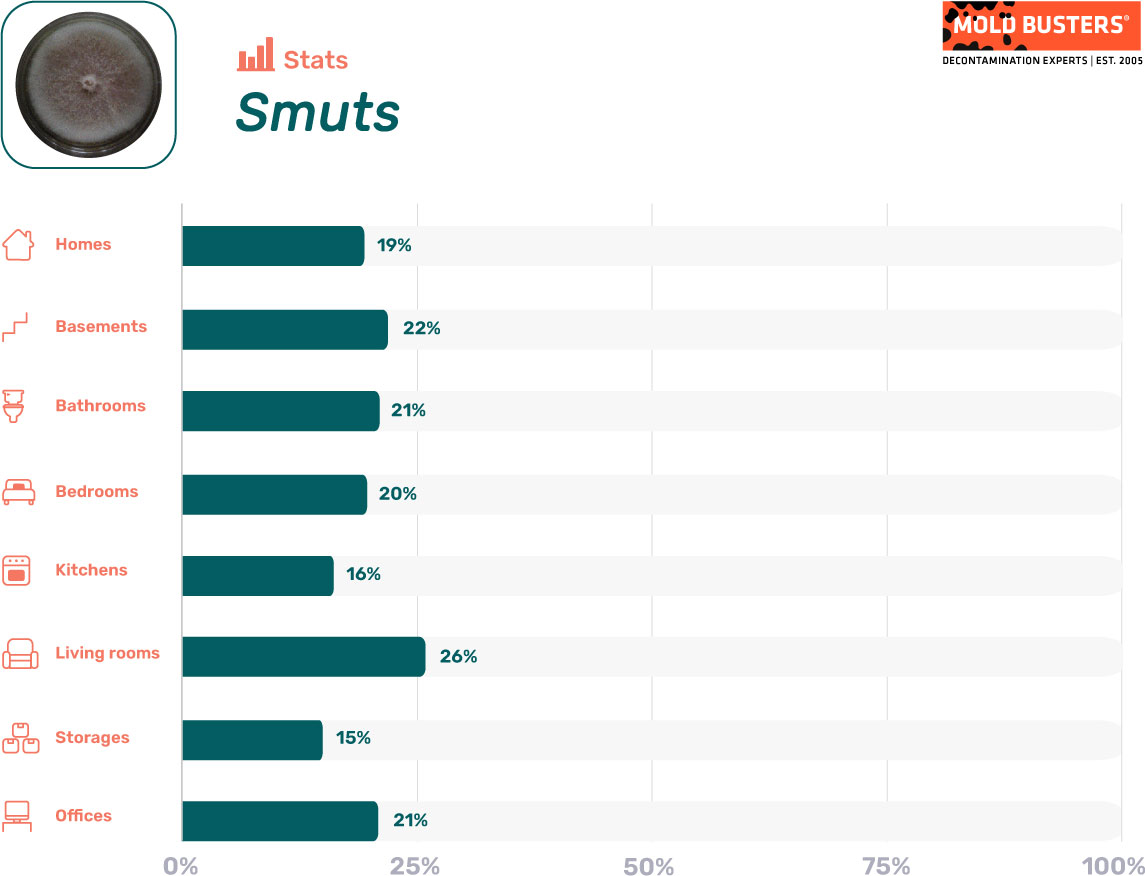

Smuts mold statistics

As part of the data analysis presented inside our mold statistics resource page, we have calculated how often mold spore types appear in different parts of the indoor environment when mold levels are elevated. Below are the stats for Smuts:

Smuts allergies

Smut spores have been known to cause allergic reactions in humans albeit rarely [3, 4]. In most cases, affected individuals work or live near farms or plantations of crops infected by smuts, or have compromised immune systems. Inhalation of smut spores has been associated with asthma, bronchitis, hay fever, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis [5]. Although this is usually an occupational hazard, it may affect people in the vicinity of farms, especially during dry and windy periods. Seasonal rises in spore count are known to occur before harvesting [6].

Like most other fungal allergies, smut allergy is likely to affect sensitive individuals, such as infants and children, the elderly, and people with compromised immune systems. Also, smut spores have a higher probability of affecting individuals who are already suffering from some type of respiratory diseases such as asthma or cystic fibrosis.

Corn smuts are prolific producers of spores. High concentrations of U. mayidism have been recorded at a level of 6000 spores per cubic meter of air, although are more often at levels of 1000 spores/m3 of air. In addition, smut spores are relatively small (~10µm), which can be advantageous as fungal pathogens [9].

What are the symptoms of smuts?

Smut spores can cause a variety of health issues if inhaled in excessive amounts. As the point of entrance for these foreign bodies are the lungs, symptoms of smut allergies are similar to those of most respiratory allergies. Common symptoms include

- coughing

- sore throat

- nasal congestion

- runny nose

- shortness of breath

- wheezing

- fever.

However, smuts are considerably less dangerous than some other fungal species such as Aspergillus, Fusarium, or Cryptococcus. They rarely cause health issues and are not known to cause any serious diseases in humans or animals.

Smuts disease

In the context of disease, smuts are mainly known for affecting plants. Although large-scale yield loss due to smut infections is rare in modern agriculture, they are still abundant plant pathogens and can be found worldwide. They are best known for affecting cereal grain crops such as maize, wheat, and barley.

During the beginning of the twentieth century, flag smut of wheat caused by Urocystis agropgri caused massive losses of wheat in Australia. The outbreak was overcome by the development of resistant wheat cultivars, and the disease is rarely found today.

Bunt or stinking smut of wheat caused by TiIIetia spp. caries also caused significant losses of wheat until certain chemicals were used to treat the seeds, controlling the disease economically and effectively. In the same period, there were numerous reports of ‘bunt explosions’ in the United States resulting from the ignition of the bunt spores that had accumulated in harvesters [7]. This can occur if the static electricity (developed by the combined machinery) ignites the teliospore dust released by the combine.

Corn smut caused by Ustilago maydis infects maize and decreases the yield. The infection causes the kernels to develop into dark-colored galls, giving the cob a scorched or burnt appearance. Interestingly, the infected galls are still edible and are considered a delicacy in Mexico (huitlacoche). As mature galls are completely dry and full of spores, the galls used for culinary use are harvested 2-3 weeks after the first signs of infection. Properly prepared huitlacoche has a flavor described as mushroom-like and is a common ingredient of quesadillas and other tortilla-based foods.

Smut diseases are generally characterized by black, dusty masses of spores. However, infected plants often display no symptoms and the spores can only be seen once the plant flowers. Many smuts infect the seeds of plants, growing quietly as the plant develops only to emerge once it is time for harvest. The fungi which cause the smut diseases are usually very specific in their selection of hosts and host organs. Some smuts may attack only one host species, and some are specialized to attack only the stems, flowers, anthers, or ovules of their hosts. Furthermore, certain species cause localized infections, while others are systemic. Many smuts are either seedling or ovary infectors [8].

What to do if you suspect smuts in your garden or backyard?

Infected plants are relatively easy to spot as they begin to develop small, whitish swellings which turn dark over time as they begin to fill with spores. Infected plants should be removed and destroyed well before the galls turn dark. They should not be composted as this will only aid the propagation of the disease. The best practice is to burn infected plants and do not plant the same species in the infected soil.

If you have any additional questions or need advice about smuts or any other type of fungus, don’t hesitate to call Mold Busters.

References

- Vánky K (2008). Smut fungi (Basidiomycota p.p., Ascomycota p.p.) of the world. novelties, selected examples, trends. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 55(2):91-109.

- Piepenbring M (2009). Diversity, ecology and sistematics of smut fungi. In: Tropical Biology and Conservation Management. Eolss Publishers, Oxford, UK.

- Wittich FW, Stackman FC (1937). A case of respiratory allergy due to inhalation of grain smuts. J Allergy. 8:189.

- Wittich FW (1939). Further observations on allergy to smuts. Lancet. 59:382-388.

- Yoshida K, Suga M, Yamasaki H, Nakamura K, Sato T, Kakishima M, Dosman JA, Ando M (1996). Hypersensitivity pneumonitis induced by a smut fungus Ustilago esculenta. Thorax. 51(6):650-1; discussion 656-7.

- González Glez Minero FJ, Candau P, González Glez Romano ML, Romero F (1992). A study of the aeromycoflora of Cádiz: relationship to anthropogenic activity. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2:211-215.

- Brown JF, Ogle HJ (1997). Plant Pathogens and Plant Diseases. Rockvale Publications, Armidale, pp 80-84

- Barnes EH (1979). The Smut Diseases. In: Atlas and Manual of Plant Pathology. Springer, Boston, MA.

- Aller Focus TM Allergen Descriptions. https://sa1s3.patientpop.com/assets/docs/113107.pdf

Get Special Gift: Industry-Standard Mold Removal Guidelines

Download the industry-standard guidelines that Mold Busters use in their own mold removal services, including news, tips and special offers:

Written by:

John Ward

Account Executive

Mold Busters

Edited by:

Dusan Sadikovic

Mycologist – MSc, PhD

Mold Busters