P. Micheli ex Haller

What is Aspergillus mold?

Aspergillus is a diverse fungal genus with high economic and health impacts. Being able to withstand elevated temperatures and low water availability, genus Aspergillus and its sexual states are one of the most widespread agents of spoilage in the world. Aspergillus spp. mostly reproduce asexually and can be isolated from most foods and raw materials. They share their habitat and thus compete with species from genera such as Penicillium and Fusarium. Fungi from the Aspergillus are used for synthesizing various compounds in the biotechnological, food, and medical industry and can also be associated with plant, animal, and human infections.

How does Aspergillus look like?

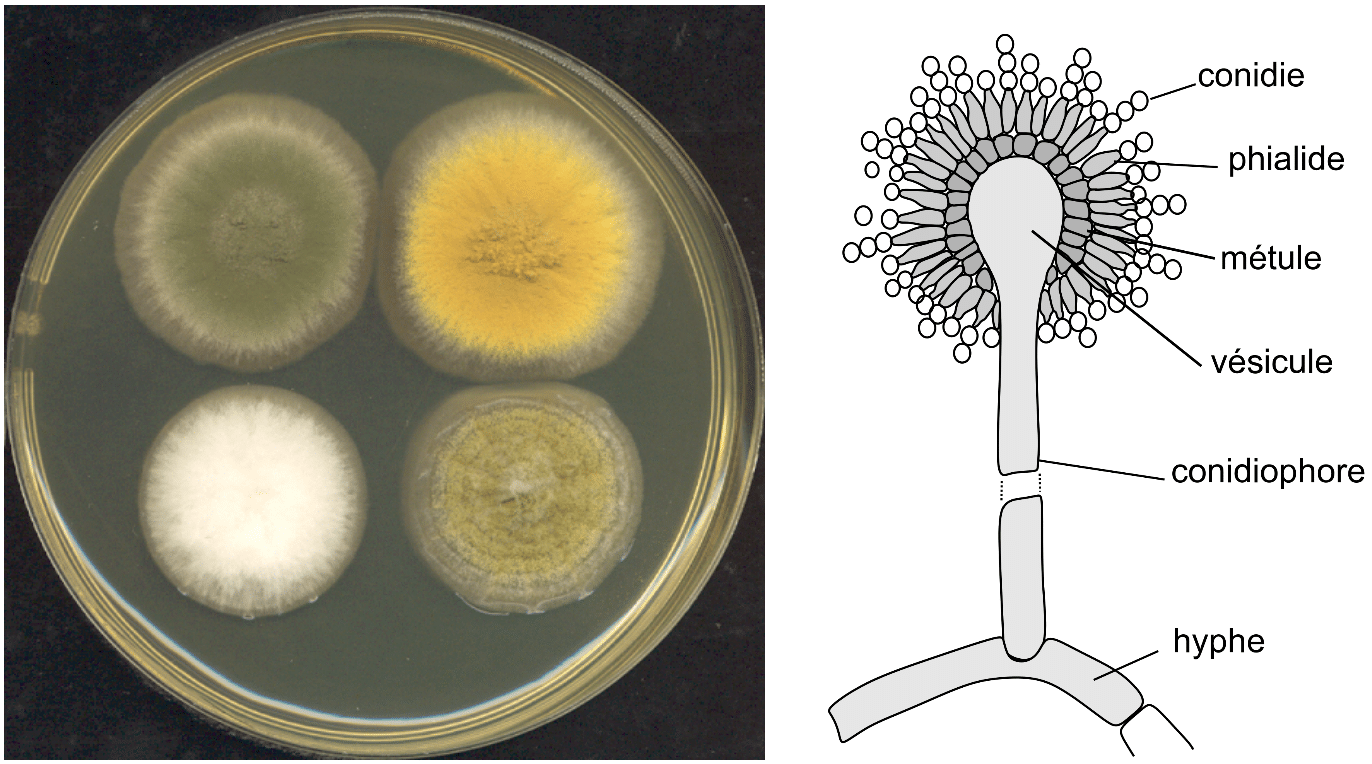

Aspergillus spp. colonies are generally fast growers, white, yellow, brown, or green. Generally, the colony surface is made up of a dense layer of erect conidiophores (spore-bearing structures) (Fig. 1). Conidiophores are non-septate and are formed from a short hypha termed a footcell. At the end of conidiophores lay a single vesicle which is generally crudely spherical, slightly elongated, or less conspicuously swollen in some species (Fig. 1). Depending on a species, the vesicle can be covered with a single layer of phialides or have an additional layer of cells called metulae. These cells bear whorls of phialides, on which the conidia (asexual spores) are formed (1,2).

The first type is named uniseriate and the later biseriate structure. If the Aspergillus species has a biseriate structure, both metulae and phialides will be formed simultaneously. Simultaneous formation of both metulae and phialides is characteristic for the Aspergillus genus, for example, Penicillium spp. form these structures individually. Vesicles, phialides, metulae, and conidia constitute the conidial head. Depending on the species, conidia are single-celled, smooth-walled or rough, hyaline or pigmented. They are produced in long dry chains which may diverge from each other or be amassed in compact columns. Some species may produce Hülle cells or sclerotia, structures that help the fungus reproduce and survive harsh conditions (1–3).

Where can Aspergillus be found?

Aspergilli, a common name used for members of this genus, are cosmopolitan and often prevalent fungal members of different ecosystems in a wide range of environmental and climatic zones. Because they can colonize many different types of substrates, aspergilli can be found throughout the Planet’s biomes, such as soil, all types of agricultural ecosystems, water ecosystems, humans, animals, and other living biota. However, aspergilli can also be found in inhospitable ecosystems such as salt marches and the Antarctic (4–6). Species such as A. fumigatus and A. terreus can be pathogenic to plants, animals, and humans, due to their lifestyle and production of mycotoxins. In contrast, many species (e.g., A. aculeatus, A. oryzae, A. niger, etc.) have applications in chemical, food, and agricultural industries for making fermented food products, organic acids, and a wide range of enzymes. For all these applications, aspergilli have been the focus of many research interests and thus hold high economic, health, and sociological values.

Aspergillus species and taxonomy

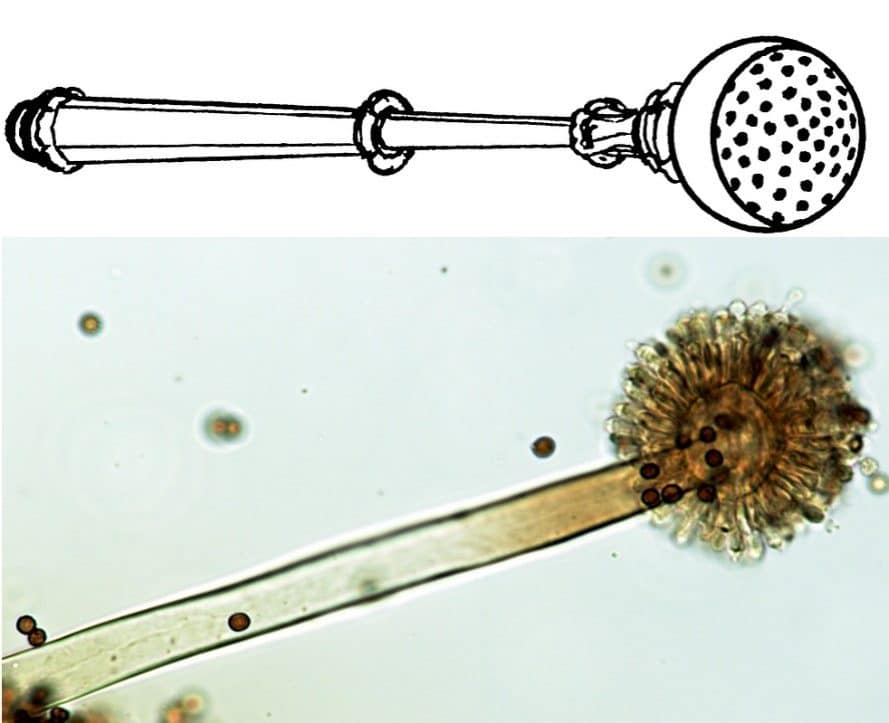

Micheli originally introduced the name of the genus Aspergillus in 1729. He aimed to describe asexual fungi that formed conidiophores, resembling an aspergillum, a device used to sprinkle holy water in Christian churches (Fig. 2) (7,8).

Aspergillus is a large genus containing about 300 species, which can be divided, based on phylogeny phenotypic and physiological characters, into six subgenera: Circumdati, Nidulantes, Aspergillus, Fumigati, Polypaecili, and Cremei (1,9). This division is also associated with the sexual states of the subgenera, where genus Eurotium is linked to subgenus Aspergillus; Sexually reproducing genera Fennellia, Petromyces, and Neopetromyces are connected with the subgenus Circumdati; Neocarpenteles, Dichotomomyces, and Neosartorya are linked to the subgenus Fumigati; Genus Emericella is associated with the subgenus Nidulantes, and genera Chaetosartorya and Cristaspora to the subgenus Cremei (1).

Some of the more notable Aspergillus species:

- Aspergillus niger – it can be found in soil and decomposing organic matter. An important source of industrial enzymes.

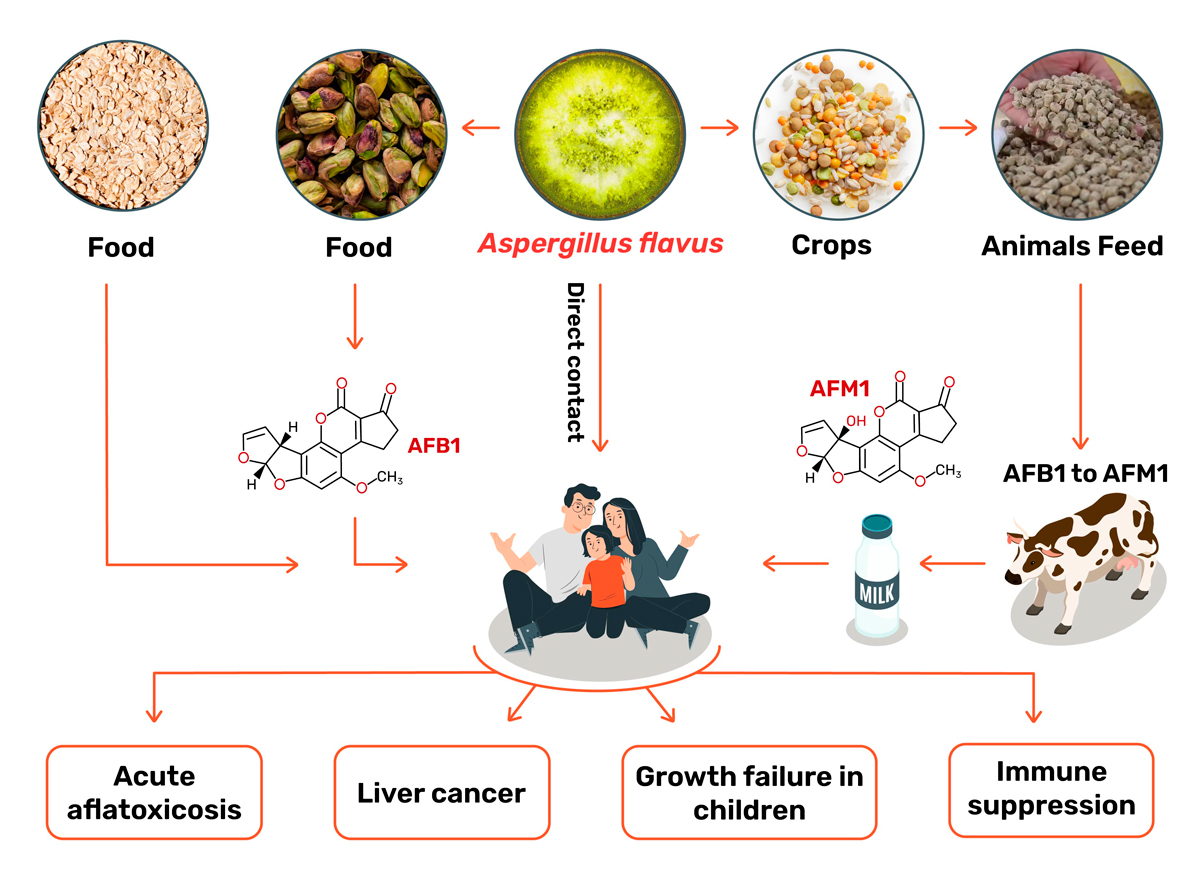

- Aspergillus flavus – naturally occurring in soil and decaying wood. It produces Aflatoxin B1 and can be pathogenic to plants, humans, and animals (Fig. 3). It can cause impaired food consumption, stunted growth, immune suppression, and possible liver cancer development in humans.

- Aspergillus fumigatus – saprophytic on plants. It can infect both plants and humans, causing invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients; It is also an allergen.

- Aspergillus oryzae – it can be isolated from healthy and plants in senescence. It has been used for centuries in fermenting soy and rice.

Aspergillus in industry

Fungal metabolites are compounds produced by the mycota and used for growth and survival. Metabolites are usually low-molecular-weight molecules that have functions such as cell signaling, enzymatic stimulation and inhibition, defense, communication, and many more. They can be divided into primary and secondary metabolites. Primary metabolites serve for the normal growth, development, and reproduction of the fungus. Secondary metabolites have versatile functions and have proven to be of great value for us. Fungal secondary metabolites have application as antimicrobial agents (antibiotics), anticancer and cholesterol-lowering drugs, immunosuppressants, antiparasitic, herbicides, etc. Aspergilli have shown various compounds, which continuously display various biotechnological perspectives (4,8).

Polyketides are perhaps the most abundant secondary metabolites produced by fungi. They are complex molecules with continuous applications in the pharmaceutical industry. Antibiotics such as doxycycline and erythromycin are polyketides. Aspergilli produce a polyketide secondary metabolite named lovastatin, which is used to control the cholesterol levels in the blood. However, aflatoxins produced by some Aspergillus species are also classified as polyketides (4,8).

The biotechnological industry heavily relies on fungi for various enzyme production. Fungi, such as aspergilli, are useful because they secrete the enzyme in the culture medium, which can be easily extracted and purified. The dark pigmented aspergilli section, especially A. niger, are heavily relied on by the various industries for the production of lipases (e.g., detergents for removal of oil stains), laccases (removal of toxic phenolic compounds), pectinases (biodegradation of plant matter, such as speeding up the extraction of fruit juices), cellulases (releasing sugars from lignin, used in practically every industry), and many more (4).

Aspergillus toxins

Aflatoxins originally came to light during the 1960s, when they caused the Turkey X outbreak, which decimated this poultry species in London, UK. What happened was that the peanut supply, used for poultry feed, was contaminated with Aspergillus flavus, an aflatoxin-secreting fungus. This resulted in the death of over 100.000 turkeys and the subsequent discovery of aflatoxins. Since then, and since the discovery of many other species of aflatoxin-producing fungi, these toxins and organisms have had great economic and medical impacts across the globe. Besides the fact that aflatoxins are non-digestible by the animals and accumulate in their meat, aflatoxins are heat and cold-resistant and remain indefinitely in the food products. When ingested, these toxins have the potential to cause cancer (carcinogenic), alter our DNA (mutagenic), disturb embryo development (teratogenic), damage our liver and kidneys (hepatotoxic and nephrotoxic), and repress our immune system (immunosuppressive) (Fig.4) (10).

Ochratoxin is another polyketide derivative and a carcinogenic fungal secondary metabolite. Various fungal species are known to produce ochratoxins, however not all of them with consistency. Among most notable are Aspergillus ochraceus, A. alliaceus, A. melleus, and some strains of A. niger. Ochratoxins contaminate grains, legumes, coffee, dried fruits, beer and wine, and meats. They can act as nephrotoxins (kidneys), carcinogens, teratogens (raise the risk of congenital disabilities), and immunotoxins in rats and likely in humans(11).

Interestingly, ochratoxins might also be behind some Egyptian mummy curses. Several archeologists who explored and uncovered certain ancient Egyptian tombs suddenly passed away due to unexplained causes. Some suggested that the cause of death might be acute kidney failure instigated by the inhalation of fungal spores containing ochratoxins. It should be noted that these explanations were just suggestions, with no yet direct evidence for this enigmatic death theory (12,13).

Aspergillus mold in our homes

The Environmental Relative Moldiness Index (ERMI) is an indoor air quality testing method developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. ERMI was designed as a reliable, standardized method to evaluate air quality and mold contamination of U.S. homes. It uses DNA-based technology to assess which adverse mold species, connected with water damage, are present in tested households. It can also give a value of their quantity. Of 36 mold species from this list, 10 belong to the Aspergillus genus. These include Aspergillus flavus, A. fumigatus, A. niger, A. ochraceus, A. penicillioides, A. restrictus, A. sclerotiorum, A. sydowii, A. unguis, and A. versicolor. These aspergilli are associated with various adverse health problems, ranging from respiratory irritations and allergens to more serious conditions such as invasive aspergillosis, pneumonia, and asthma.

Aspergillus mold statistics

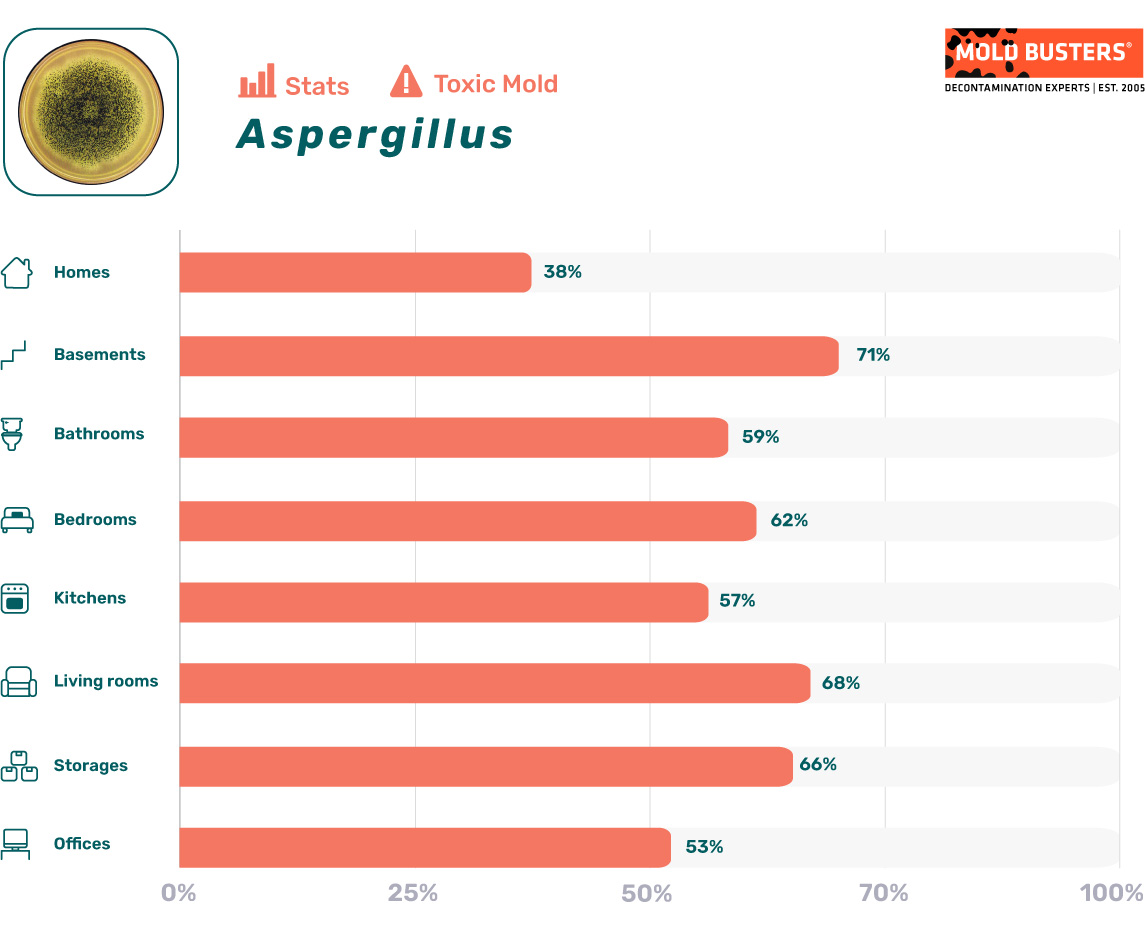

As part of the data analysis presented inside our mold statistics resource page, we have calculated how often mold spore types appear in different parts of the indoor environment when mold levels are elevated. Below are the stats for Aspergillus:

References:

- Samson, R. A., Visagie, C. M., Houbraken, J., Hong, S. B., Hubka, V., Klaassen, C. H., … & Frisvad, J. C. (2014). Phylogeny, identification and nomenclature of the genus Aspergillus. Studies in mycology, 78, 141-173.

- Aspergillus | Mycology Online. Available from: mycology.adelaide.edu.au

- Pitt, J. I., & Hocking, A. D. (2009). Fungi and food spoilage(Vol. 519, p. 388). New York: Springer.

- Abdel-Azeem, A. M., Abdel-Azeem, M. A., Abdul-Hadi, S. Y., & Darwish, A. G. (2019). Aspergillus: biodiversity, ecological significances, and industrial applications. In Recent Advancement in White Biotechnology Through Fungi(pp. 121-179). Springer, Cham.

- Butinar, L., Frisvad, J. C., & Gunde-Cimerman, N. (2011). Hypersaline waters–a potential source of foodborne toxigenic aspergilli and penicillia. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 77(1), 186-199.

- Arenz BE, Blanchette RA, Farrell RL. Fungal diversity in antarctic soils. Antarct Terr Microbiol Phys Biol Prop Antarct Soils. 2013 Dec 1;35–53.

- Micheli P. Nova plantarum genera

- Tsang, C. C., Tang, J. Y., Lau, S. K., & Woo, P. C. (2018). Taxonomy and evolution of Aspergillus, Penicillium and Talaromyces in the omics era–Past, present and future. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 16, 197-210.

- Houbraken, J. A. M. P., & Samson, R. (2011). Phylogeny of Penicillium and the segregation of Trichocomaceae into three families. Studies in mycology, 70, 1-51.

- Amare, M. G., & Keller, N. P. (2014). Molecular mechanisms of Aspergillus flavus secondary metabolism and development. Fungal Genetics and Biology, 66, 11-18.

- Bayman, P., Baker, J. L., Doster, M. A., Michailides, T. J., & Mahoney, N. E. (2002). Ochratoxin production by the Aspergillus ochraceus group and Aspergillus alliaceus. Applied and environmental microbiology, 68(5), 2326-2329.

- Bayman, P., & Baker, J. L. (2006). Ochratoxins: a global perspective. Mycopathologia, 162(3), 215-223.

- Di Paolo, N., Guarnieri, A., Loi, F., Sacchi, G., Mangiarotti, A. M., & Di Paolo, M. (1993). Acute renal failure from inhalation of mycotoxins. Nephron, 64(4), 621-625.

- Vesper, S., McKinstry, C., Haugland, R., Wymer, L., Bradham, K., Ashley, P., … & Friedman, W. (2007). Development of an environmental relative moldiness index for U.S. homes. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 49(8), 829-833.

- Vesper, S., Wakefield, J., Ashley, P., Cox, D., Dewalt, G., & Friedman, W. (2011). Geographic distribution of Environmental Relative Moldiness Index molds in USA homes. Journal of environmental and public health, 2011.

Get Special Gift: Industry-Standard Mold Removal Guidelines

Download the industry-standard guidelines that Mold Busters use in their own mold removal services, including news, tips and special offers:

Written by:

Dusan Sadikovic

Mycologist – MSc, PhD

Mold Busters

Fact checked by:

Michael Golubev

General Manager

Mold Busters